Why do we burn gas in our homes?

Carbon Choices UK author, Neil Kitching, makes the case to use electricity, rather than gas, in our homes—for carbon health and energy security reasons.

Householders and businesses in the UK face a stark choice: heat their homes from ‘natural’ gas OR from electricity. At present 85% choose, or more accurately default to, natural gas.

Where does this gas come from? How does it get to your home?

History of Home Heating

Not so long ago we burnt coal to heat our homes. Miners drilled and dug this heavy material from deep coalmines in the UK, often working in dirty and dangerous conditions. Lorries transported the coal to our coal sheds. Every day we cleared out the ash, lit the fire and shovelled coal into our living rooms.

In most cases the fire only heated one or two rooms at best. The smoke was bad for indoor air quality. Burning coal created ‘acid rain’.

Then the great smog in London in 1952 resulted in around 10,000 excess deaths. The Clean Air Act was subsequently introduced in 1956 to reduce the amount of smoke pollution and sulphur dioxide. Smokeless coal was introduced.

The oil crisis of the 1970’s resulted in an accelerated search for oil and gas in the North Sea. Gas was a cleaner fuel than coal; it was piped into our homes, and could be combined with hot water distribution pipes to produce ‘central heating’.

Given a choice between coal or gas, it was an easy choice to make. Householders who were unlucky enough not to be near the new gas grid either continued to burn coal or switched to electric storage heaters. These heaters were ‘charged’ at night at cheap electricity rates. However, the early storage heaters were not very flexible, and often ‘ran out’ of heat by the evening.

Modern storage heaters are better designed, and can benefit from access to flexible tariffs, however they are still more expensive to run than gas.

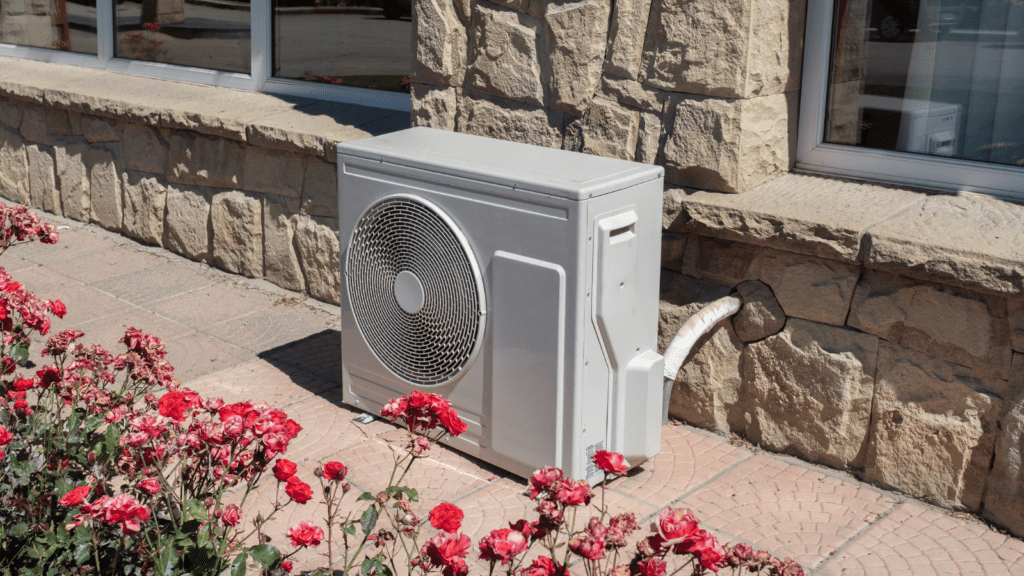

Heat Pumps

Heat pumps are a ‘new’ heating technology for the UK. They absorb ambient energy from outside and by doing so can produce around three times the amount of heat as the electricity required to run them. Their running costs are cost competitive with gas, especially if combined with solar pv or flexible electricity tariffs. Their carbon emissions are three times less than that of burning gas, and this is improving all the time as the UK grid decarbonises (target of 2030 for a carbon free grid).

So, why don’t we all have a heat pump? Why do we bring a potentially explosive gas into our house for heating and cooking which creates indoor air pollution by emitting nitrous oxide into our homes?

Lots of reasons are given to avoid or delay a decision to buy a heat pump including their high capital cost, the need to install larger radiators, lack of knowledge or confidence in a ‘new’ technology, and concern around repairs and maintenance. Ultimately, most of us are familiar with burning natural gas and don’t see any urgency to change.

Once you have installed a heat pump, the energy market discriminates against you. Electricity costs are ‘artificially’ high because we pay the marginal cost of the most expensive generation (often gas) and because there are levies added to electricity bills which are not added to gas bills. The Government could (and should) choose to address these anomalies.

How is gas produced?

Gas is a natural, but non-renewable substance created millions of years ago by tiny organisms being buried in sediments, with subsequent decay and burial. Seismic surveys are used to identify pockets of underground gas. In suitable locations a drilling rig, or gas platform, if in the sea, is built. Production wells drill into the rocks with gas pumped up to the surface.

An alternative method is to frack shale rocks. Water with some sand and chemicals is pumped under pressure into the rocks forcing the gas out to the surface. Whilst this process is banned in the UK, it is common in the USA.

Gas is then processed to remove contaminants, stored, then pressurised and piped to our homes via the gas network. An alternative long distance transport method is to cool the gas to -160oC so it becomes liquid then transport the reduced volume liquified gas by ship to the UK, where the liquification process is reversed back to gas and fed into pipelines.

Carbon Emissions

We should look at the entire lifecycle to compare the carbon emissions of burning gas or using electricity in our homes.

For gas:

- carbon dioxide emitted as you burn gas in your home

- emissions from pumping and distributing gas through pipelines to our homes

- constructing the infrastructure to extract and process gas, e.g. from the North Sea and pipelines

- emissions from producing gas, including methane leaks.

For electricity:

- emissions from generating electricity

- transmitting and distributing electricity to our homes (pylons and sub-stations)

- constructing the infrastructure to generate electricity (coal, gas or nuclear power stations, hydro, solar and wind).

The Government helpfully publishes annual figures for the carbon emissions from burning gas or using direct electricity in your home. In 2023 they were similar at 0.20kg/0.21kg CO2e per unit respectively. Emissions from transmission and distribution are included in the emission factor for electricity. But emissions from burning gas never change, whilst those from electricity are declining as the UK transitions to renewables. Already today a heat pump, with a 300% efficiency, will emit only one-third of the emissions of using gas. Heat pumps are therefore far cleaner than natural gas.

The embedded emissions from constructing gas rigs and electricity power stations, wind turbines or solar are much harder to calculate. These may seem large but are relatively small if distributed over the lifetime of the assets (I can’t find good figures on this, although one report suggested that for gas power stations it would be around 10% of total lifetime emissions, whilst it would be less than half of this for wind and solar).

But producing gas has an additional operational component compared with using electricity (unless produced from burning gas). In the UK in 2021, 14.5 million tonnes of CO2e were emitted to extract and process oil and gas in the North Sea basin. These emissions arise from the power required to operate oil and gas rigs and from flaring and venting of methane. This venting of methane (80x worse than carbon dioxide) can add significantly to the environmental impact of gas. In addition, methane can leak from storage and the distribution network.

It is estimated that these emissions add another 6% to the total emissions of burning gas in your home. But this is an average for the UK. Pipeline imports from Norway (with few methane leaks) are the most ‘efficient’ at 3% whilst imports of LNG by ship are four times as carbon intensive (24%). This is due to the extremely energy intensive process of liquefying natural gas and transporting it by tanker.

Conclusions

We are accustomed to burning natural gas in our homes despite its dangers and climate impact. It is relatively cheap. However, increasingly our gas is being imported, with LNG imports having an even higher carbon footprint associated with their transportation.

Heat pumps are cleaner and greener. They can be deployed in individual houses or, in high density areas, large heat pumps can efficiently heat multiple homes using district heat pipes. This is our future.

Neil’s book, Carbon Choices on the common-sense solutions to our climate and nature crises, is available direct from http://www.carbonchoices.uk/index.php/buy. Neil is donating one third of profits to rewilding projects.

Republished with permission from: http://www.carbonchoices.uk/index.php/blog/blog-60

Looking for more info on how we can work together to live more sustainably? Find more Glimmer articles here.

Join the Glimmer community—people who care about helping each other to live more sustainably. Because together we can make a difference.