The Makings of Change: COP28, Climate Anxiety and Hope for the Future

Last year’s United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP28) made headlines across the world, but the question remains: will it achieve real, tangible progress?

Well, it certainly broke some records!

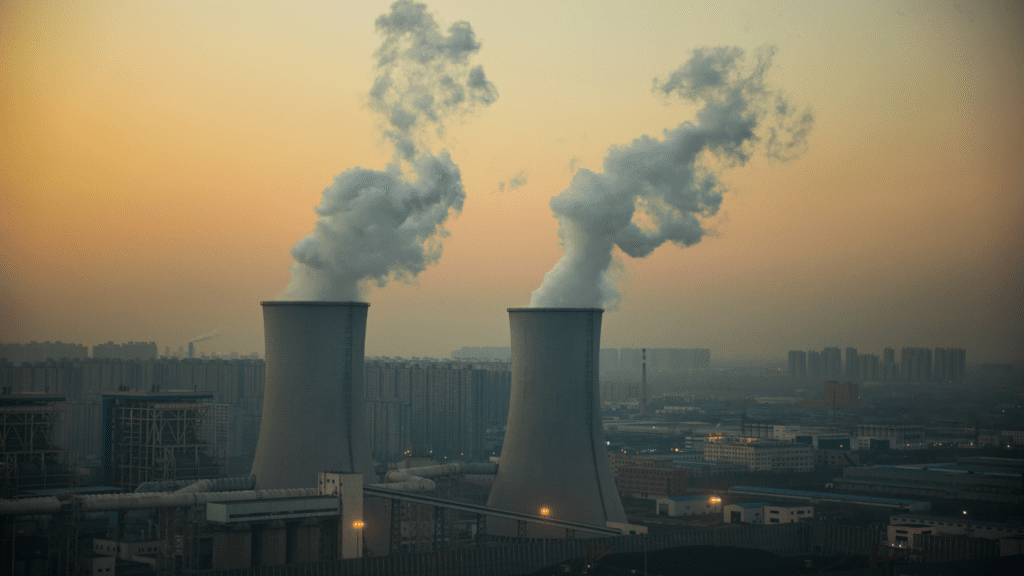

Unfortunately, the broken record in question relates to the turnout of fossil fuel lobbyists, of which there were 2456 in attendance. Add to that at least 340 meat and dairy lobbyists, 475 carbon-capture lobbyists and a president who also happens to be an oil company executive; it’s no surprise the talks resulted in pledges to do something-or-other about fossil fuels eventually, maybe.

That’s not to say that the summit didn’t achieve anything of worth—an international agreement to reach net zero by 2050 is definitely better than nothing. But, without a concrete plan to get there, it’s not that much better. It’s particularly disheartening when even the president of the conference himself, UAE’s Sultan Al Jaber, intends to continue his company’s oil production in the hopes that the invisible hand of the market will solve the climate crisis. And here I was thinking that was his job…

To its credit, the summit resulted in, among other agreements, a decarbonisation charter, damage and loss funding, and a global stocktake. Each of these has its own set of strengths and limitations; for example, the damage and loss funding is managed by the World Bank, whom many developing countries are understandably sceptical of. Still, this is progress, nonetheless.

The outcome of the summit is encapsulated in the UAE Consensus, which states that the world must “transition away from fossil fuels in energy systems in a just, orderly and equitable manner, accelerating action in this critical decade, so as to achieve net zero by 2050 in keeping with the science.”

This looks good on paper, even if it feels a few decades late amid the hottest summer on record (hey, look at us, breaking records all over the place!).

Considering the concept of atmospheric carbon dioxide levels increasing the Earth’s surface temperature has been floating around since at least 1896, it’s easy to be critical of this agreement, which promises—or, rather, encourages—a long overdue bare minimum. As Madeleine Diouf Sarr, Chair of the Least Developed Countries Group, put it, “It reflects the very lowest possible ambition that we could accept.”

Despite the United Nations’ lack of ambition, the blunt reality is that the climate is changing, often with disastrous consequences. Nonetheless, global action remains insufficient to keep warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius by the end of the century. This should not be surprising to anyone—it is not a new narrative. This has been the case for decades. The only difference is that now climate change is no longer some amorphous, future threat; it is a brutal present-day reality that many across the world are forced to contend with daily.

In light of this reality and our seeming powerlessness to make a difference, it’s easy to feel pessimistic about the future of our planet. Our news media is flooded with stories of crisis, disaster and conflict, in part because sensationalism sells and, in part because the climate crisis is a genuine threat deserving of our attention. Still, it’s hard, at times, not to feel drained by empathy, or else grow cold and cynical. Considering the tone of this blog so far, I’m certainly in no place to judge anyone for being cynical. It’s easy to feel that there’s no hope, and that change is impossible.

The blunt reality, however, is that hopelessness benefits no one. Pessimism may be tempting, but it isn’t useful. It is self-indulgent. We need to face climate change head-on, accept the, at times, disheartening reality of it, and continue the fight regardless. The first step towards making change is accepting that it is possible.

Importantly, change comes in many different shapes and sizes. As individuals, we can do what we can to live sustainably—reduce our meat consumption, be more conscious about the ways we commute, and power our homes through more sustainable energy sources, such as solar power. We can also financially support positive sustainability initiatives and avoid financial institutions that contribute to fossil fuel production and other sources of pollution.

It’s easy to feel as though small steps like these won’t make a difference on a global scale, but many small, sustained lifestyle changes can add up to a very great change indeed. And at the end of the day, the only actions you can control are your own.

However, climate change is not merely a symptom of individual choice; it is the result of a global economic system that prioritises profit over human well-being. So, we need to hold governments and corporations accountable—even more so than individuals. At a global, systemic level, we need to move away from fossil fuels in our energy systems—though I’m sure you could’ve guessed that one at this point! To achieve this, we need to actively challenge the practices of major polluters, rather than hoping they’ll change their ways through some spontaneous burst of altruism.

The fossil fuel industry has a long history of publicly denying—and internally affirming—the scientific consensus around climate change. If COP28 is anything to go by, not much has changed. If we want to hit fossil fuel corporations where it hurts, we need to target their bottom lines—perhaps through a carbon tax that forces them to pay for the damage they are doing to the environment, or at the very least through a reduction in fossil fuel subsidies in favour of renewables.

It’s important to remember that the need for action at a government and corporate level does not absolve us of our individual responsibilities to live more sustainably. Likewise, individual lifestyle changes are not a replacement for systemic change. They are two sides of the same coin, and they are both necessary if we want to create a more sustainable world.

Indeed, there is an important intersection between systemic and individual change. For instance, the environmental degradation that accompanies modern consumerism—think e-waste or fast fashion, for example—has led to support for alternative economic models, such as circular economies and degrowth. These models require rethinking our global economic systems, but they also call for individual lifestyle changes, moving away from excessive consumerism and towards simpler, more sustainable ways of living.

Inevitably, corporations will ignore the climate crisis as long as it is profitable for them to do so. If we want to reduce global emissions, we need to change the profit structures that contribute to pollution. This requires government action and thus public support. Under that lens, climate pessimism and hopelessness become vital mechanisms that maintain the status quo.

We need to be careful not to let climate anxiety cripple us. Instead, we should let it fuel our drive to change, to pursue more sustainable ways of living. In this way, small, seemingly futile individual changes can become radical acts of protest against political ambivalence and hopelessness.

- About the Author

- Latest Posts